by John Sadler

One of the most notable historians of Anglo-Scottish Border conflicts, John Sadler has published a number of books on the subject and is also a successful lecturer, heritage consultant, historical interpreter and battlefield tour guide. ‘From an early age I have been obsessed with the highlands and borders.’ he says, ‘Since then I have travelled, walked, ridden and driven over most of the ground and looked at every battlefield, hillfort, broch, dun and castle.’

One of the most notable historians of Anglo-Scottish Border conflicts, John Sadler has published a number of books on the subject and is also a successful lecturer, heritage consultant, historical interpreter and battlefield tour guide. ‘From an early age I have been obsessed with the highlands and borders.’ he says, ‘Since then I have travelled, walked, ridden and driven over most of the ground and looked at every battlefield, hillfort, broch, dun and castle.’

Sadler regularly lectures at The National Army Museum, Imperial war Museum, RMA Sandhurst, Heriot Watt University, Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle upon Tyne, The Literary and Philosophical Society, Newcastle, Durham University, the DLI Museum & Art Gallery and contributes to many military and historical journals as well. He is a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society, a Fellow of Scotland’s Society of Antiquaries, a graduate Holocaust Fellow of the Imperial War Museum and a member of Equity.

STEEL BONNETS

Episode 1

Wha daur meddle wi’ me?

Wha daur meddle wi’ me?

My name is little Jock Elliot,

And wha daur meddle wi’ me?

The reivers are ours; that’s the thing. When you re-enact Wars of the Roses, the Civil Wars or D-Day, those conflicts belong to all. But the moss-troopers are all ours, well ours and the Scots of course; we spent three long and bloody centuries debating the point. Naturally, you need the right kit; a sturdy border garron is always a handy, if a rather time consuming and expensive accessory. Much of your Civil War gear, if you’re not too prissy, is easily recycled, shirt, breeches, doublets, and those long leather thigh boots you wouldn’t dare wear in the Bigg Market of a Friday evening. Breast and back, burgonet with rapier, backsword and dudgeon, all good; longbow and matchlock both in service, you’re dressed to rob.

The reivers are ours; that’s the thing. When you re-enact Wars of the Roses, the Civil Wars or D-Day, those conflicts belong to all. But the moss-troopers are all ours, well ours and the Scots of course; we spent three long and bloody centuries debating the point. Naturally, you need the right kit; a sturdy border garron is always a handy, if a rather time consuming and expensive accessory. Much of your Civil War gear, if you’re not too prissy, is easily recycled, shirt, breeches, doublets, and those long leather thigh boots you wouldn’t dare wear in the Bigg Market of a Friday evening. Breast and back, burgonet with rapier, backsword and dudgeon, all good; longbow and matchlock both in service, you’re dressed to rob.

When England and Scotland were at last united under a single Crown in 1603, these two countries had been at war, outright or simmering, for three hundred years, since the time of William Wallace and the Wars of Independence, beginning in 1296.

During the 16 th Century there were times of intense, open warfare between the two. Scotland had long been an ally of England’s old enemy, France. Indeed, in 1512 the ‘Auld Alliance’ between these two countries was extended, and all nationals of Scotland and France also became nationals of each other’s countries, a status not repealed in France until 1903.

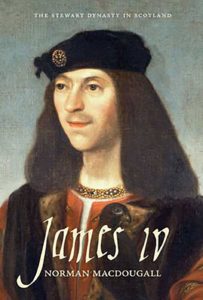

In the following year (1513) this allegiance obliged James IV of Scotland to attack the English in support of his French allies, who had been attacked by Henry VIII. The result was Flodden, in which the Scottish king, many of his nobles and perhaps ten thousand men were killed – The Flowers of the Forest of the folk song. The Scots like a good whinge of course and if it’s all the fault of the English then that’s a bonus. As for James IV he wasn’t that romantic, just a rather silly man who’d read all the manuals but hadn’t got the small-print.

And things did not improve over the century. After a period of regency, James V of Scotland succeeded his father and married a French noblewoman, Mary of Guise, mother of his only daughter, Mary. In 1542, James’ rag tag army was soundly and humiliatingly trounced at the Battle of Solway Moss in another disastrous campaign against the fucking English. He died shortly afterwards. Henry VIII failed in his ensuing diplomatic and then military attempts to win the hand of James’ young daughter Mary (to be Queen of Scots) for his son Edward (to be Edward VI) – the so- called Rough Wooing that continued into the regency that followed Henry’s own death in 1547. Mary had been sent to France, aged five, as intended bride of the French Dauphin. She might have done rather better had she stayed there.

The Border country … was the ring in which the champions met; armies marched and counter-marched and fought and fled across it; it was wasted and burned and despoiled, its people harried and robbed and slaughtered, on both ides, by both sides. Whatever the rights and wrongs, the Borderers were the people who bore the brunt; for almost 300 years, from the late thirteenth century to the middle of the sixteenth, they lived in a battlefield that stretched from the Solway to the North Sea.

The Border country … was the ring in which the champions met; armies marched and counter-marched and fought and fled across it; it was wasted and burned and despoiled, its people harried and robbed and slaughtered, on both ides, by both sides. Whatever the rights and wrongs, the Borderers were the people who bore the brunt; for almost 300 years, from the late thirteenth century to the middle of the sixteenth, they lived in a battlefield that stretched from the Solway to the North Sea.

Who were these Reivers?

Check out the annual Border gathering in the Scottish West March. It’s not often, in slashed doublet, multi-coloured hose and those boots that I feel underdressed but compared to US visitors avid for evidence of border roots I was a mere beginner in the sartorial stakes. Only difference was I was aware I was in costume; never did so few behold so many in such bizarre variations of ‘clan’ attire, peacock feathers and maxi-kilts in luminous shades abounded. Disconcerting when one confesses he’s a state executioner in civvy-street. The apparently insatiable thirst for family history fuels these gatherings, a substantial slice of invisible earnings to boost the border economy and evidence the current generation have moved from sheep to fleecing overseas tourists.

Then, this harsh land north and south of the Border was a region of ‘riding names’, groups held together by the most powerful of all bonds – blood. Thus, not only was Northumberland subject to cross-border incursions from the Scots, but also to inter- clan raiding. Indeed, the Border Line itself meant little to the reivers: The raiders from Bewcastle, from Tynedale and from Redesdale were as much a nuisance to their compatriots as was anyone from over the Border. Indeed, at the time compatriot meant nothing and the Border did not count for much, for men who had made the place too hot to hold them on one side would flee to kinsmen and friends on the other, being “Scottish when they will and English at their pleasure.

They weren’t very nice people, these ancestors of course, they regularly hewed their victims in pieces, they drank a lot would have smoked and done drugs had these been available, let us thank God the AK47 hadn’t been invented. Reivers (from the OE rēafian – to rob) were not all ‘outlaws’, although some of them most certainly were.

They came from all classes and backgrounds, having in common the ability to ride and to fight and the need to survive in a hostile environment. Marauding reivers carried out cattle-thieving raids with impunity, both across the border and against their neighbours, knowing that the rule of law simply did not apply in their dales. It was an accepted way of life. Practising systematic thievery and wholesale destruction, they have the dubious distinction of bringing the word bereaved into the English language, as indeed they did blackmail, another innovative reiver practice.

By the sixteenth century, robbery and blood feud had become virtually systematic, and that century saw the activities of the steel-bonneted Border riders – noble and simple, robber and lawman, soldier and farmer, outlaw and peasant – at their height.

This wasn’t the good old days, not a shade of woad in sight; it was nasty, poor, very brutish and even more often short. Many a scion of the riding names choked out his life on some impromptu gallows, unless he had to be drowned where sufficient rope could not be found and, after all, hangmen have fees and the river is free.

In other words, we are not talking here about a set of villains who were perpetually attacking their peace-loving countrymen. Theft was the principal business of everyone in the region. It was simply a way of subsisting during the reiving ‘season’ from late August to February (Candlemas) whenever weather and moonlight allowed: A foray might involve a dozen riders or half a thousand, with the graynes* active every night the weather allowed, the bright reivers’ moon their guiding star.

So important was this lunar conspiracy that the image appears in border heraldry – the Scott’s badge was a star and two crescent moons; mottoes such as ‘we’ll have moonlight again’ were popular amongst riding names.

Not long ago I found myself posturing on horseback and, of course, in full kit, narrating a History Channel episode on Flodden Field. As quirky is in at present, pontificating from the saddle, assuming I could remain seated, seemed like a good idea. It was at least a score of summers since my backside last reposed on horseflesh, and this one was feisty enough for sure. Still, the look is all, forget the quivering bowels and think upon attitude. Damn me and it was good though, to be alive on those border hills astride a latter day garron, the rise and sweep of dun coloured uplands spreading before like a benediction, no hint of modernity, (aside from the film crew and a plethora of 4WDs), just the lonely haunting of a curlew and an annoying cameraman or two. I get paid for this?